In the Clean Break Archive: Clean Break’s Building

Head down Kentish Town Road from the tube station, and take a left on Patshull Road. Next to the Jobcentre, you’ll see a little alleyway. Go all the way down the alleyway. Clean Break has the big wooden gates at the end. Ring the bell and we’ll buzz you in.

It has been more than a decade since I first walked up the cobbled alleyway to Clean Break’s studios in London’s northwest borough of Kentish Town, where the company’s building nestles like an open secret between the commercial high street and private homes. The studios can be hard to find, and when found, have something of a protected rampart about them, with impossible-to-scale solid gates. In some ways it may appear counterintuitive to encounter a perimeter guarding studios in which theatre is created and taught precisely on principles of personal freedom and social change. The gates provide a protection from real dangers – keeping the building invite-only is critical to keeping it a safe space for Members who attend Clean Break’s theatre programme, many of whom are the victims of crime themselves, and survivors of domestic violence and abuse. Yet the building is actually anything but cloistered: from the first floor up in any of the surrounding properties, there are unobscured views into the company’s gardens. A soundscape of laughter, chatting, singing and shouts from women in the garden achieves a radical bounce off the surrounding walls.

Clean Break’s building is at the very heart of the company’s work. Yet how did Clean Break get here?

At the entrance of the building, a plaque announces:

Image taken at opening event on 17 March 1999 by Sarah Ainslie.

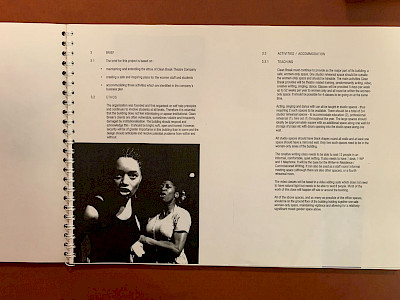

Clean Break’s archives show that 1998-1999 was a momentous, movement-filled year of both adjustment, and celebration, for Clean Break. The company had been growing at a steady pace, increasing its operations and educational programme as well as the scale of its theatre productions; by the mid-nineties, it was chafing at the size restrictions of its rented offices at 37/39 King’s Terrace in Camden Town. Perhaps even more crucial than the consideration of size, was the need for space aligned to the purpose, and ethos, of the company. Company members began to strategise what a new home for Clean Break would look like, how it would perform, and the ways in which it would provide shelter. In a brief to architects to describe their aims for a new, purpose-built space, they wrote: ‘The organisation was founded and first organised on self-help principles and continues to involve students at all levels. Therefore it is essential that the building does not feel intimidating or appear institutional. Clean Break’s clients are often vulnerable, sometimes volatile and frequently damaged by institutionalisation. The building should respond and acknowledge this – it should be bright, soft, open and honest.’

Avanti Architects, Design Brief.

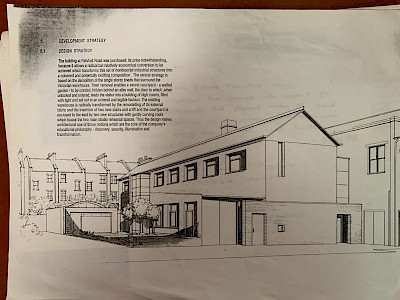

In 1995, Clean Break had an offer accepted on a light industrial building in Kentish Town, dating to the Victorian period. The proposed architectural project, which included the creation of three new studio spaces within the existing structure, as well as demolishing some of property’s built space, faced some concerns from neighbours. Although the nature of these concerns is not specified in Avanti Architects’ report, the architects note that modifications were made to parking, planting in the courtyard, and ‘design and specification of the glazing’, which could indicate concerns around sound travelling from the building. The architects also note substantial support within the neighbourhood for Clean Break’s proposal. (Avanti Architects brief section 5, ‘planning issues and current situation’)

Avanti designed the garden space as a ‘secret courtyard – a walled garden – to be created, hidden behind an alley wall, the door to which, when unlocked and entered, leads the visitor into a building of high rooms, filled with light and set out in an ordered and legible fashion…. mak[ing] architectural use of those notions which are at the core of the company’s educational philosophy – discovery, security, illumination and transformation.’

Avanti Architects, 5.1 Design Strategy.

Housed within this refurbished nineteenth century factory, Clean Break’s three studios went on to host a full roster of theatre education, from courses in costume, acting, playwriting, and devising, to stage management, stage design, make-up and lighting; and to provide the rehearsal and performance space for dozens of Clean Break plays. The studios reflect a non-institutional atmosphere, in deliberate contrast to the design protocols of prison environments. There are overt resistances to domains of discipline throughout the building: huge windows in the common areas, allowing for circulation of air, light and people, as well as many areas that are private, with no opportunity for observation.

In addition to these spatial efforts to facilitate free movement and creativity, the building carries a temporal echo of performance through its history affiliated to music and fashion, first as one of the many piano factories of Camden and Kentish Town from the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and then as a tie factory in the early days of Christian Dior. When Clean Break purchased the premises in 1995, the building was derelict and long decommissioned as a source of employment for the community. This palimpsest of performance, discipline, resistance and employment within Clean Break’s building carries powerful meaning when also considered as a continuum of precarious social conditions, between difficult conditions of factory work, lack of employment, and prisons for the working-class poor. Along these same lines, in its repurposed use the building also defiantly protests conditions of dispossession, proposing a space to be imagined and inhabited by those who, as women imprisoned or at risk, have had their right to property contested, removed or threatened. It also protests against what is considered ‘security’ and what is considered acceptable identity within capitalist configurations of personhood via property, in which the protection of property is valued above the protection of life.

what’s she building in there by Laura Dean, a retranslated photo of Clean Break premises under construction 1998 with retranslated footage of production [BLANK], Donmar Warehouse, London 2019.

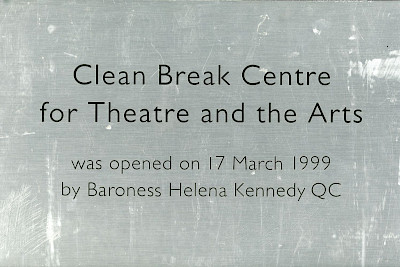

This is Where We’re From

Clean Break moved into its new premises in August 1998 and celebrated the new building with a launch event hosted by Baroness Helena Kennedy QC on 17 March 1999. That evening, a keynote was given by broadcaster and later head of the Commission of Racial Equality, Trevor Phillips OBE. A Report from the Clean Break Management Committee in 1999 praises this event as ‘surrounded by much positive media attention reflecting the Company’s new higher profile’; a rich volume of images of the event in the Clean Break archive document the evening as filled with performances and speeches in the new studios, and under the night sky.

Clean Break building opening contact sheet, image: Sarah Ainslie.

In October 2014, fifteen years after the opening of the building, Clean Break Members devised and performed This Is Where We’re From, a promenade piece that took visitors through Clean Break’s building and gardens. The play was one of over 100 ‘Fun Palaces’ created around the UK to celebrate Joan Littlewood’s centenary. British theatre director Joan Littlewood held a passionate belief that ‘good theatre draws the energies out of the place where it is and gives it back as joie de vivre’ (in Ezard and Billington 2002). For This Is Where We’re From, the cast of twelve students researched and performed events from the lives of women who lived locally to Kentish Town and Camden: Mother Red Cap (a purported witch known as ‘The Shrew of Kentish Town’), prison reformer Elizabeth Fry, and Edith Garrud, a martial arts practicing suffragette who developed ‘suffrajitsu’ in the early 1900s. Each main area of Clean Break’s ground floor (and main staircase) hosted a scene and musical number that reached across decades and centuries to briefly summon these courageous, committed, and publicly scorned women back to their local digs. In the final scene, ‘All the Women’, created and performed with directors Suzy Davies, Vishni Velada-Billson and writer Morgan Lloyd Malcolm, the ensemble gathered in the courtyard garden to sing:

All the women who’ve stood up before us

I’m from their fury from their fight […]

It’s down to me

It’s down to us

To keep their life from dying

we will justify their struggle and strife

It’s down to me

It’s down to us

To never ever stop trying

We will justify their struggle and strife […]

Every daughter, sister, mother and wife

We will justify their struggle and strife.

(You can listen to All the Women on Soundcloud).

Standing in the courtyard as an audience member, I thrilled to the sight of neighbours all around coming out onto their balconies to listen and watch the women perform. I thought of the astounding fourteen party wall property agreements these neighbours made, so Clean Break could build a centre to help women recover, make theatre, celebrate their lives and successes, find work, and dream. Most of all, I thought of the tremendous gift these women offered to their neighbours, in being here.

In ‘All the Women’, standing in the Clean Break courtyard, all these women shout out their provenance:

I am from the crashing seas of chaos and confusion

I am from the place of no cuddles

I am from a place of violence, punched and locked out

I am from the hopes of those who stood for me

I am from a warm place, inside my mum

I am from here

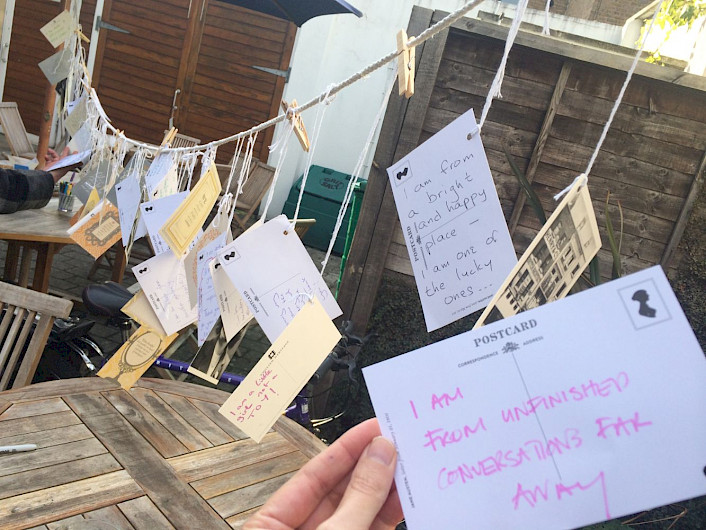

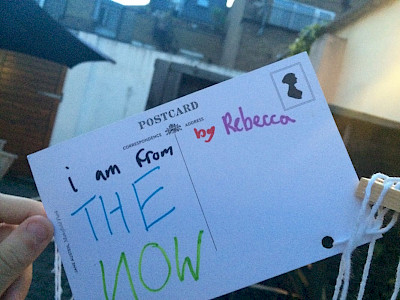

Following the performance, the audience share their provenance too:

Images of audience postcards, 5 October 2014.

The moment powerfully demonstrated not only the support for Clean Break Members in the immediate community, but a liminal convergence of community and criminal justice, buildings saturated with lived lives past and present, and – most of all – theatre’s ability to draw these strands into a crucible of performance that scrambles, reshapes, and reinvests perceptions of how women are caused to enter, and indefinitely remain, in the criminal justice system. We are from here – this place, down an alleyway between the jobcentre and private homes – and in this place, the then is part of the now, as we contest a carceral system that seeks (and fails) to destroy memory, as much as it does future.

This Is Where We’re From cast in Clean Break’s foyer.

Dr Molly McPhee is a researcher in theatre and criminal justice, based at Queen Mary University of London, and a former General Manager for Clean Break (2009-2015). You can learn more about Molly's work on our collaborators page.